“How Did They Ever Make a Movie of Lolita?”

The Romanticisation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita in Film and Online Spaces, and Its Influence on Identity Construction and Cultural Perception

By Romany S. Rawlings

Adapted from a dissertation originally submitted to King’s College London for the BA in Comparative Literature with Film, 2025.Content Note: This essay contains discussion of sensitive and potentially distressing topics, including paedophilia, grooming, child sexual abuse, and child pornography. Reader discretion is advised.Copyright Notice: © Romany S. Rawlings, 2025. This essay includes film stills and social media screenshots reproduced under UK Fair Dealing (Section 30) for the purposes of criticism and review. All third-party materials are used for analytical purposes only.

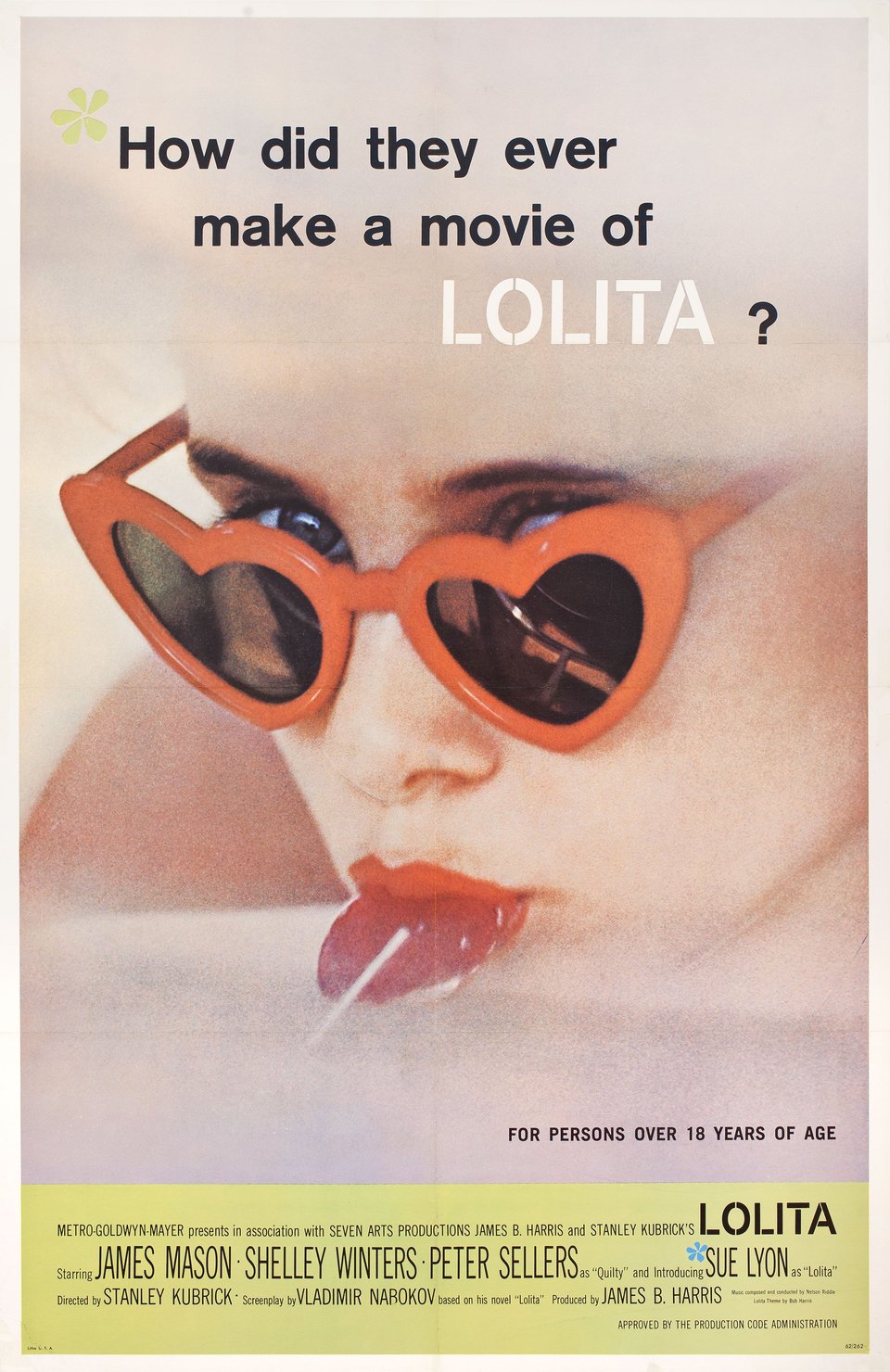

“How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?”, the tagline for Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel, continues to encapsulate the enduring cultural unease and fascination surrounding the translation of Lolita from literature to film and icon. This question, though perhaps not intended by Kubrick to bear such weight, highlights not only the aesthetic and narrative challenges of adapting a linguistically intricate and morally ambiguous text for the screen, but also the broader ethical implications of doing so. Adrian Lyne’s 1997 adaptation further reignited debates over the representation of Nabokov’s subject matter, foregrounding tensions between artistry, censorship, and morality. Both films, despite their stylistic and tonal differences, have played pivotal roles in cultivating a legacy of romanticisation around Lolita, a legacy that continues to shape how visual and digital cultures reinterpret, commodify, and distort the novel’s profoundly unsettling core.

Published in 1955, Lolita is presented as the fictional memoir of Humbert Humbert, an incarcerated man recounting his obsessive and exploitative relationship with twelve-year-old Dolores Haze, whom he nicknames “Lolita.” Framed as a posthumous confessional, Humbert’s narrative relies heavily on self-justification, unreliability, and literary manipulation, making Nabokov’s novel notoriously difficult to adapt without compromising its critical distance. While Nabokov’s prose is layered with irony and moral ambiguity, its cinematic adaptations, and later online appropriations, have often flattened these complexities into a romanticised aesthetic that reframes the narrative’s disturbing core.

This essay explores how the romanticisation of Lolita, turning something morally grey or ambiguous and reframing it with ideas of beauty, has developed through its major film adaptations and subsequent digital reinterpretations, considering how these visual and cultural reimaginings contribute to a wider process of aestheticising abuse and reconfiguring identity. By examining Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 and Adrian Lyne’s 1997 adaptations alongside the novel itself, the discussion highlights how each work negotiates Nabokov’s tension between beauty and horror, irony and sentimentality. Furthermore, it considers how the visual culture surrounding Lolita, particularly within online spaces such as Tumblr and TikTok, has transformed the figure of “Lolita” into an emblem of stylised innocence and transgression, detached from the novel’s critique of manipulation and violence.

Ultimately, this essay argues that the cultural repackaging of Lolita, from literature to film to digital icon, has contributed to the persistent romanticisation of harmful dynamics. By tracing how Nabokov’s work has been reinterpreted across visual and online media, the analysis reveals the unsettling endurance of Lolita as both a symbol of desire and a reflection of society’s complicity in aestheticising exploitation.

To fully understand the persistent misrepresentation of Lolita, it is first necessary to consider the novel in its original literary context. Published in 1955 by the French publishing house Olympia Press, a company notorious for its avant-garde and often provocative titles, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita was initially rejected by several American publishers who deemed it too controversial. European publishers, by contrast, were more receptive to works that combined eroticism with irony and satire. Nabokov later recounted these rejections with wry humour: “Publisher X, whose advisers were so bored with Humbert that they never got beyond page 188, had the naivety to write me that the book was too long. Publisher Y, on the other hand, regretted that there were no good people in the book. Publisher Z said if he printed it, he and I would go to jail.” Despite this early resistance, Lolita rapidly gained notoriety after Graham Greene listed it among the best novels of the year in the Sunday Times. The backlash was immediate, both Greene and the Times were accused of promoting pornography, and the novel was subsequently banned in the United Kingdom and France before its eventual publication in the United States in 1958.

Nabokov maintained that Lolita was neither pornographic nor political, describing it instead as a “pure” artistic endeavour. Yet it is difficult to take this claim entirely at face value. While Nabokov resisted moral or didactic interpretations, Lolita cannot be divorced from the cultural anxieties it provoked about obscenity, censorship, and artistic freedom. His insistence on aesthetic autonomy seems, in part, to operate as a form of self-justification, an attempt to distance himself from the moral panic surrounding his work while maintaining intellectual control over its reception. As Elizabeth Janeway noted in her 1958 review, Lolita is “one of the funniest and one of the saddest books that will be published this year,” and “few volumes [are] more likely to quench the flames of lust than this exact and immediate description of its consequences.” Nabokov’s prose thus achieves a paradoxical duality: sensuous in form yet deeply critical of sensuality’s destructive potential. His refusal to separate the “aesthetic” from the “immoral” invites readers to confront their own discomfort, exposing the fragile line between beauty and exploitation.

The now infamous opening line of the novel sets the precedent for the entirety of Lolita, where Humbert proclaims, “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul,” immediately establishing a tone of obsession and possession, where the nickname “Lolita” becomes both the first and last word of the text, enclosing the narrative within Humbert’s fixation. The lyrical, carefully constructed rhythm of the line, composed during Humbert’s time in prison, draws the reader into his mind and his facade. Just as “Lolita” is the last thing on Humbert’s mind, it becomes the last thing on the reader’s as well, situating us within his obsessive, circular thought patterns. Stylistically, the opening is rich in alliteration and melodiousness. Repeated sounds ‘L’, ‘o’, ‘a’, ‘m’, and ‘s’ roll softly and smoothly off the tongue, creating an almost hypnotic effect. This beauty belies the disturbing content that lies ahead. Humbert, as an unreliable narrator, presents himself as charming and poetic from the outset, sugar-coating the narrative and manipulating the reader into sympathising with him.

The line’s use of the word “fire” evokes imagery of something uncontainable and all-consuming, suggesting the intensity of his desire and, by extension, the destruction it causes. Fire, as a motif, appears elsewhere in Nabokov’s work, most notably in Pale Fire, and consistently symbolises obsession and engulfing passion. Furthermore, when Humbert describes Dolores as his “sin” and his “soul,” he metaphorically absorbs her into his own identity. This duality of repentance and possession reveals the depth of his delusion: he frames himself as a tragic, tortured figure, thereby attempting to elicit sympathy from the reader. By naming her as both a transgression and a salvation, Humbert positions Dolores as integral to his psyche, further blurring the line between obsession and justification.

Yet, it is the nickname Lolita itself that is perhaps most crucial in understanding the tragedy of the novel. By renaming Dolores Haze, Humbert transforms a real child into a fantasy construct. No other character calls her by this name; she is “Dolly” or “Lo” to others, and in her later letter she signs herself “Dolly (Mrs. Richard F. Schiller),” reclaiming a measure of her identity. “Lolita” thus becomes a tool of objectification, a linguistic act that diminishes Dolores into a projection of Humbert’s desire. Were the novel titled Dolores, the reader might encounter a story of a girl with her own agency; instead, Lolita is situated forever within the confines of Humbert’s gaze. The title itself symbolises the theft of her identity and voice, the process through which language enacts possession.

This objectification is further reinforced through the motif of the “nymphet,” a term Humbert himself defines: “Between the age limits of nine and fourteen there occur maidens who, to certain bewitched travellers, reveal their true nature which is not human, but nymphic (that is, demoniac).” The phrase “bewitched travellers” is particularly revealing. Humbert portrays himself as a passive figure, enchanted, even victimised, by the supposed supernatural power of these young girls. This inversion of agency, in which the child is imagined as seductress and the adult as helpless, echoes dangerous cultural narratives still invoked to excuse predatory behaviour. By attributing his desire to enchantment, Humbert reframes coercion as compulsion, thus absolving himself of responsibility.

The term “nymphet” itself carries dual etymological resonances. In entomology, a nymph is the sexually immature form of an insect that resembles the adult, a state of arrested development. Nabokov, a lifelong lepidopterist, may have been drawn to this scientific metaphor to rationalise Humbert’s obsession: the nymphet as an incomplete being, suspended between childhood and womanhood. Simultaneously, the word evokes Greek mythology, where nymphs are minor deities associated with nature, beauty, and erotic allure. In classical literature, those who encounter nymphs are often “bewitched” into madness, overcome by uncontrollable eros. Humbert’s description of nymphets as “demoniac” borrows from this tradition, suggesting his desires are not chosen but inflicted upon him. This mythologisation, like the scientific language he employs, intellectualises predation and shifts blame onto the victim, transforming violence into a tragic destiny.

Both the entomological and mythological strands reveal Humbert’s fixation on stasis. In both science and myth, nymphs are frozen in perpetual youth, incapable of maturity. Humbert’s ideal, therefore, is not a real person but an unchanging fantasy. His attraction to women such as his first wife, Valeria, whom he admired for her childlike imitation, demonstrates the futility of this obsession. Once she begins showing the physicality of an adult woman, “down turned to prickles on a shaved shin,” Humbert’s fascination wanes, as the illusion of innocence dissolves. His desire depends on the impossibility of time standing still; thus, it is doomed from the outset.

Through Humbert’s manipulative narration, Nabokov exposes the mechanisms of self-delusion and moral evasion. Humbert’s insistence that he is a “bewitched traveller” and a victim of love is revealed as linguistic theatre, a performance that disguises cruelty as art. Nabokov’s refusal to offer explicit moral guidance leaves the reader complicit in navigating this ambiguity, forced to confront how easily beauty and eloquence can obscure exploitation. Whether Nabokov’s disavowal of political or moral intention was sincere or strategic remains open to interpretation. What is certain, however, is that Lolita endures precisely because of this tension: it compels readers to question not only Humbert’s justifications, but also their own susceptibility to them.

In his writing, Vladimir Nabokov demonstrates remarkable artistry through the lyricism and precision of Lolita, particularly in his ability to construct a narrator who embodies equal parts charisma and malevolence. As Roxane Gay writes in her essay Ugly Beautiful, “In a lesser writer’s hands, Lolita would have been vulgar… But Nabokov is deft in every choice he makes in telling Humbert Humbert’s story… It is an incisive examination of a paedophile’s downfall and the people he takes along with him.” Gay’s observation raises a difficult question: can great writing redeem the morally reprehensible? Nabokov’s prose seduces the reader through linguistic beauty, but that very seduction mirrors Humbert’s manipulation, forcing us to confront the ethics of aesthetic pleasure. The problem arises when later adaptations reproduce the beauty of Lolita’s surface while neglecting the critical self-awareness that underpins Nabokov’s artistry.

Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 Lolita, starring James Mason and Sue Lyon, represents the point at which Lolita became less a critique of obsession and more an object of obsession itself. Notably, Nabokov initially wrote the screenplay, which Kubrick heavily edited, prompting the author’s famous complaint that viewing the final product was like “a scenic drive as perceived by the horizontal passenger of an ambulance.” The film’s tagline, “How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?” poses an ironic question, for the more fitting one might be: Did they ever make a movie of Lolita?

Figure 1. Promotional poster for Kubrick’s Lolita (1962), featuring the iconic imagery that contributed to the visual codification of Lolita.

Kubrick’s adaptation and its marketing material transformed Nabokov’s complex novel into a romanticised and aestheticised product. The promotional image of Sue Lyon wearing red heart-shaped sunglasses and sucking a lollipop, shot when she was only fourteen, became iconic, eclipsing Nabokov’s explicit opposition to depicting a young girl at all. “There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to,” he insisted, “any kind of representation of a little girl.” Yet this image came to define Lolita, conflating Dolores with the sexualised fantasy of her abuser and thus realising Humbert’s delusion in visual form.

As Rachel Arons of The New Yorker observes, “Once this image became associated with Lolita… it really didn’t matter that it was a terribly inaccurate portrait. It became the image of Lolita, and it was ubiquitous.” The cultural afterlife of this image has been profound. Dieter E. Zimmer catalogued over 200 Lolita book covers from around the world, most featuring sexualised depictions of young girls or women styled to look juvenile. Kubrick’s film thus fulfilled Humbert’s fantasy by turning Dolores into a willing seductress, a distortion that undid Nabokov’s careful crafting of a story about victimisation and self-delusion. Importantly, however, this sexualisation is not unique to Lolita; Hollywood’s history is littered with examples of underage actresses objectified under the guise of artistic daring. Lolita merely crystallises this pattern into its most explicit form, exposing the industry’s willingness to aestheticise youth and vulnerability.

In my earlier draft, I extended a charitable reading to Kubrick, suggesting the impossibility of fully translating Lolita’s layered irony to film. On reflection, however, this generosity may be misplaced. The film’s aestheticisation was not an unavoidable by-product of adaptation but a deliberate choice. Producer James B. Harris admitted, “We knew we must make her a sex object… where everyone in the audience could understand why everyone would want to jump her.” This statement makes clear that Kubrick’s Lolita was marketed through the same logic that Humbert uses to justify his actions: intellectualising desire, aestheticising abuse, and erasing the victim’s suffering. Even the censorship constraints of the 1960s, which forced the filmmakers to age Dolores from twelve to fifteen, served not to protect her but to legitimise her objectification. Lyon, heavily made up and styled as an adult, appeared closer to eighteen. As critic Peter Green noted, she “looked imperious, knowing, and appeared to be at least 18; she is not, as Nabokov describes in the book, ‘standing four feet ten in one sock.’” The film’s presentation of an older, complicit Dolores blurs the ethical boundaries that Nabokov so carefully delineated. Lyon herself later suffered the consequences of this distortion, her career stunted and her image permanently tied to a sexualised role she was too young to control. The production, in this sense, became an unsettling mirror of the novel’s themes: men profiting from the exploitation of a girl under the guise of art.

Figure 2. Sue Lyon in Lolita (1962) exemplifies the film’s deliberate ageing and sexualisation of Dolores Haze through mature styling choices such as makeup, coiffed hair, and a robe. Lyon’s pose, lying on her side with the robe slightly raised, evokes a consciously provocative image that underscores the film’s controversial framing of her character.

Kubrick’s adaptation is therefore more than a misreading; it is a real-world enactment of Humbert’s logic. Humbert famously claims that only “certain bewitched travellers” can perceive the rare species of “nymphet,” asserting that “only true geniuses” can recognise such creatures. This declaration epitomises his intellectualisation of predation: by recasting his desire as a form of aesthetic insight, he transforms moral deviance into elevated understanding. This mechanism, what psychoanalytic theory would call intellectualisation, uses reason and artistic rhetoric to evade confrontation with guilt and emotional conflict. Kubrick’s film, and indeed Hollywood’s wider treatment of youth and sexuality, participates in this same process. The industry’s insistence on artistic daring serves as a collective rationalisation that masks exploitation behind the veil of sophistication.

Adrian Lyne’s 1997 adaptation, starring Jeremy Irons and Dominique Swain, inherits many of Kubrick’s ethical contradictions. Lyne’s version is visually lush and emotionally intense, but, like its predecessor, it collapses Nabokov’s critical distance. The film positions the audience within Humbert’s gaze, rendering Dolores the object of voyeuristic pleasure. Early scenes, such as Humbert’s first sight of Dolores sunbathing under a sprinkler, are shot from behind foliage, as if the camera itself were a predator. The film’s use of the eyeline match invites viewers to share Humbert’s perspective, blurring moral boundaries. While Lyne avoids explicit sexual content, the camera’s lingering attention on Swain’s body replicates the problem it seeks to condemn. As Final Girl Digital on YouTube argues, “these girls have acted as sacrificial lambs in order to benefit the egoic pursuits of grown men.” The use of real child actors for such narratives, even under claims of artistic integrity, raises inevitable ethical concerns.

Lyne’s Lolita, like Kubrick’s, aestheticises what Nabokov meant to disturb. Gay’s notion that “the aesthetics of Lolita… undo or at least diminish the ugliness of the story they represent” captures the core of this failure. In literature, Nabokov’s exquisite prose implicates readers in Humbert’s delusion only to expose their complicity; in film, beauty becomes spectacle rather than critique. The medium’s visual immediacy erases the ambiguity that Nabokov relied on to force moral discomfort. Both adaptations thus repeat the very tragedy they should resist: they render abuse palatable, the grotesque desirable, and the victim invisible. Nabokov’s Lolita was a study in how art and intellect can be used to rationalise evil; its filmic afterlives, disturbingly, prove the point.

Adrian Lyne’s 1997 adaptation, starring Jeremy Irons and Dominique Swain, inherits many of Kubrick’s ethical contradictions while updating them for a late-twentieth-century audience. Lyne’s version, released in a culture ostensibly more open about sexuality, was no less controversial. Its distribution was delayed due to its subject matter, with many cinemas refusing to show it. Screenwriter Stephen Schiff defended the film by arguing that depicting paedophilia did not equate to endorsing it, just as a film about murder does not promote murder. Yet this analogy is flawed. As YouTuber Final Girl Digital notes, “to compare them [murder and paedophile] is redundant. Murder is exclusively a physical act; by assimilating murder on screen, you are not partaking in murder... However, paedophilia is not exclusively physical. People can, and often do, engage in paedophilia without physically touching children. This can commonly take place in the form of child pornography.” In this light, even without explicit scenes, the decision to use a fifteen-year-old actress to depict a victim of abuse is inherently exploitative.

Lyne’s Lolita foregrounds sensuality and, like Kubrick’s, risks collapsing its moral distance. The cinematography is lush and romantic, filled with golden light and languid close-ups that blur the line between tragedy and desire. The camera frequently adopts Humbert’s point of view, positioning the audience as voyeurs. When Humbert first sees Dolores sunbathing beneath a sprinkler, the shot is framed through bushes, the lens literally peering through foliage as if stalking prey. This Edenic imagery, sunlight, water, nature, renders Dolores as an object of innocence and temptation, a nymphet in paradise. The scene’s beauty is undeniable, but it functions as seduction, drawing the viewer into Humbert’s fantasy. The use of eyeline matches and lingering camera movement reinforces this alignment between viewer and predator, creating what Laura Mulvey would describe as the male gaze, a structure that privileges looking as an act of possession. Roxane Gay’s insight that “the aesthetics of Lolita… undo or at least diminish the ugliness of the story they represent” is especially pertinent here. Nabokov’s prose entices readers into complicity only to expose it, ensuring that moral discomfort persists beneath the beauty. Lyne, however, transforms that discomfort into visual pleasure. His adaptation blurs the line between critique and indulgence, collapsing Nabokov’s delicate irony into sentimentality. The result is a film that seems aware of its own moral danger but remains entranced by it.

Ultimately, both Kubrick’s and Lyne’s adaptations exemplify how easily Nabokov’s display of manipulation becomes a blueprint for it. In literature, Humbert’s narrative is confined by the page, his charm a matter of words from the serpent's mouth that relies on the reader’s awareness of his deceit. On screen, that barrier dissolves. The visual medium’s immediacy encourages belief in what is seen, not scepticism toward who is showing it. Kubrick’s and Lyne’s Lolitas thus reveal the peril of aestheticising immorality: the grotesque becomes desirable, the victim aestheticised, and the abuser humanised.

Nabokov’s original novel remains morally troubling; it is, after all, narrated by a man who intellectualises his crimes, but it sustains its complexity by never allowing the reader to forget that the beauty is a mask. The adaptations, by contrast, strip away this mask and mistake the artifice for truth. In doing so, they replicate the very logic Humbert employs to seduce: that art and intellect can justify anything if rendered beautifully enough.

When considering the visual representation of Lolita, its imagery is often more immediately accessible than the text itself. Stills from the film adaptations circulate online detached from Nabokov’s irony or critique, allowing the visual narrative to eclipse the literary one. When directors such as Kubrick and Lyne frame Humbert and Dolores’s relationship as a love story, this misreading becomes cemented, and its imagery, heart-shaped sunglasses, lollipops, and pastel Americana, becomes shorthand for a stylised kind of forbidden romance. Online, this accessibility allows for the rapid circulation and transformation of Lolita’s imagery. On platforms like Tumblr and TikTok, these aesthetics have been repurposed into trends that romanticise the novel’s darkest themes, giving rise to the “Nymphet” and “Coquette” subcultures.

Emerging in the early 2010s, the Tumblr “Nymphet” community celebrated vintage Americana, hyper-femininity, and references to age-gap relationships. Its iconography, stills from Lolita, pink bedrooms, knee socks, lollipops, reduced Nabokov’s prose to a visual identity. Numerous posts titled “How to Be a Nymphet” instructed young users on how to embody Dolores Haze’s supposed charm, positioning youth as a form of power and seduction. The platform’s melancholic, performatively aesthetic culture made this romanticisation appear not only acceptable but desirable. Although the 2018 adult content ban erased much of this material, its influence persists in the later “Coquette” aesthetic popularised on TikTok.

Figure 3. Humbert Humbert’s first encounter with Dolores Haze (played by Dominique Swain) in Lolita (1997). This image has been widely circulated since the film’s release: Dolores, visible through wet clothing, is framed from Humbert’s point of view, through the bushes of the garden, creating a voyeuristic perspective that aligns the audience with his gaze.

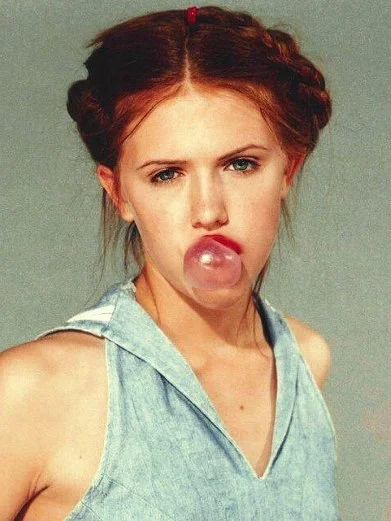

The Coquette trend of the 2020s retained many of the same qualities: fragility, innocence, and hyper-femininity expressed through frills, gloss, and coy self-presentation. Yet, this time, the aesthetic was bound up with virality and no longer a small subculture. Videos tagged #Lolita often show users dressed as Dolores, lip-syncing to dialogue from the film adaptations or songs like Lana Del Rey’s Lolita. One particularly notable example is a TikTok by @branxkarinita, which has over 1.1 million likes, where the creator imitates Dolores’s look from the 1997 film, milkmaid braids, halter top, blowing bubble-gum pink, visually recreating her image. While such videos might appear self-promotional, I would argue that they are also aspirational: the aesthetic itself becomes a route to online popularity. The ability to gain visibility through the performance of “Lolita-ness” turns victimhood into a kind of desirable identity, one that merges consumption with self-fashioning.

Figure 4. Screenshot from a Nymphet-themed Tumblr blog featuring a still from Lolita (1997), exemplifying the aestheticisation of the character Dolores Haze in online subcultures. Figure 5. Screenshot from a TikTok video by user @branxkarinita, mimicking the style of Dolores Haze and exemplifying the modern revival of the Lolita aesthetic through the coquette trend. Figure 6. A still of Dolores Haze from the 1997 adaptation of Lolita, whose styling and pose were recreated by @branxkarinita, reflecting the continued visual influence of the film in online spaces.This transformation of abuse into aesthetic reflects a wider cultural trend where innocence is eroticised and commodified. As Lawrence Ratna notes, “The image of the sexually provocative Lolita seductively sucking a lollipop as she gazes out over red heart-shaped glasses has become a cultural icon of the child as an object of male desire.” This process extends beyond Lolita itself. In popular culture, figures like Fiona Apple, Britney Spears, and Kesha were similarly marketed through an uneasy fusion of adolescence and sexuality. When Apple released her debut album Tidal at nineteen, the music video for Criminal presented her in her underwear amidst childhood relics, stuffed toys and floral wallpaper, framing her as both child and seductress. The video’s voyeuristic lens left audiences, as critics observed, feeling they had watched something close to child pornography. Despite Apple’s consent, she later expressed discomfort, saying the experience was “a huge step for me, personally, because I’m not comfortable doing any of that.” Scholar Shari L. Savage captures this tension aptly: “Popular culture’s Lolita is a girl ready-made for pursuit, a girl who will be sexually desired while at the same time condemned for her sexuality.” This contradiction, of being both desired and shamed, sits at the heart of the “Lolita Effect,” a term describing how media sexualises young girls while obscuring adult culpability.

Such portrayals blur the boundary between critique and consumption. The Nymphet and Coquette aesthetics transform Nabokov’s tragedy into a lifestyle, one in which girlhood is aestheticised and performed rather than understood. As studies on the “Aesthetic Self Effect” suggest, what we present outwardly shapes who we become; thus, adopting the Lolita aesthetic is not merely stylistic but formative. Identity becomes entangled with self-objectification, and beauty with subjugation.

Kate Elizabeth Russell’s My Dark Vanessa (2020) offers a powerful counterpoint to this culture of romanticisation. Told from the perspective of a survivor reflecting on her teenage abuse, Russell’s novel dismantles the seductive myth of Humbert’s narrative. In her Afterword, Russell writes that in the late nineties and early 2000s, “Lolita was a term used to describe the girls I idolised: Fiona Apple, Christina Ricci, Britney Spears. I saw how men my father’s age ogled Anna Kournikova.” She admits that Lolita once sat on her nightstand beside Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, novels she believed were “cut from the same cloth—full of obsession and abuses.” Her reflection encapsulates the danger of misreading: how narratives of grooming, when romanticised, can infiltrate collective ideals of love and desirability.

The online and cultural afterlives of Lolita reveal how easily critique becomes a commodity. Through repetition and aestheticisation, Dolores Haze is transformed from victim to archetype, from person to performance. Aestheticisation does not neutralise violence; it disguises it. When young women style themselves as “Lolitas,” they are not reproducing Humbert’s crimes in intent, but in form: re-enacting a narrative of exploitation as a means of visibility, connection, and control in a digital culture still shaped by the male gaze.

Nabokov’s Lolita has, over time, been transformed into the very thing it sought to critique, a romanticised portrayal of abuse refracted through the aestheticised lens of its cinematic adaptations. In both Kubrick’s and Lyne’s adaptations, Humbert’s voice is no longer questioned but echoed; the manipulative language and unreliable narration that once exposed his deceit are replaced by images that sustain his fantasy of “Lolita” as the willing seductress. Through visual motifs such as the now-iconic heart-shaped sunglasses and directorial framing that aligns the audience with Humbert’s gaze. Styling, costume, and performance choices further age up Dolores, making her the object of fascination rather than sympathy. In doing so, the films transform a narrative about manipulation into an image of romance, establishing the visual foundations for Lolita’s later cultural mythologisation.

This distortion has extended beyond cinema into digital culture, where the “Lolita” figure has been repackaged into the ‘Nymphet’ and ‘Coquette’ aesthetics that dominate online spaces such as Tumblr and TikTok. These subcultures do not merely draw inspiration from Nabokov’s text but reimagine its iconography as a mode of self-presentation. Here, girlhood becomes a performance of fragility, innocence, and seduction, a carefully curated image through which identity and desirability are constructed. Yet this construction is deeply troubling. By aestheticising the sexualisation and infantilisation of young women, these trends normalise harmful power dynamics and blur the boundary between victimhood and desirability. What emerges is a culture that encourages young girls to conflate being desired with empowerment, and to romanticise the very structures that objectify them.

Perhaps, however, this transformation is not entirely at odds with Nabokov’s own artistic paradox. Though he maintained that Lolita was written for “personal artistic expression” rather than moral instruction, the novel’s migration into physical and visual media seems to render that neutrality impossible. Once a work enters the visual sphere, aestheticisation becomes inevitable; what was once filtered through Humbert’s unreliable narration is now seen, literalised, and consumed. No one wants to make an ugly movie. The act of seeing itself introduces an ethical tension: perhaps there is no entirely ethical way to represent this story, particularly when told through the eyes of the abuser. Literature allows for ambiguity, irony, and self-deception; cinema, by contrast, invites surface reading. Thus, when Lolita became image rather than text, it became aesthetic at face value, its critique absorbed by its own beauty.

In this sense, the continued romanticisation of Lolita reveals how visual and digital cultures transform critique into commodity, turning the language of abuse into the aesthetics of attraction. The persistence of the “Lolita” image underscores the power of media to shape identity, but it also exposes the danger of mistaking artistic expression for ethical clarity. By embodying the predatory gaze rather than challenging it, contemporary reinterpretations of Lolita demonstrate that the line between critique and complicity may not only be thin but also impossible to sustain once the story becomes visual. Perhaps this is Lolita’s final irony: a novel that sought to expose delusion has itself become one. In loving the image more than the warning, culture has made Humbert’s fantasy immortal, proof that even the clearest critique can be consumed by the beauty it tries to condemn.

⋆.ೃ𐦍*:・⋆𐦍.ೃ࿔*:・

──── ۶۟ৎ ────

⋆.ೃ𐦍*:・⋆𐦍.ೃ࿔*:・ ──── ۶۟ৎ ────

Bibliography

Arons, Rachel. “Designing Lolita.” The New Yorker, 2013. Read here

Badenes-Sastre, Marta, et al. “Cognitive Distortions and Decision-Making in Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review.” Psychosocial Intervention, vol. 34, no. 1, 2024, pp. 23–35. DOI:10.5093/pi2025a3

Book Marks. “Sick, Scandalous, Spectacular: The First Reviews of Lolita.” Literary Hub, 2020. Read here

Bran, Karina. “#Lolita.” TikTok, 2021. Watch here

Burns, Astrid. “Feelin’ Like a Criminal: Fiona Apple and the Lolita Effect.” McLeod Writing Prize, Washington University in St. Louis, 2024. PDF available here (openscholarship.wustl.edu)

Coquetteswan. “It Was Love at First Sight, at Last Sight, at Ever and Ever Sight.” Tumblr, 2023. View post

Dey, Maitrayee. “Tumblr Statistics and Facts.” Electro IQ, 2025. Read here

Demongeot, Catherine. Allocine Profile, 2007. View photo

Dulcissimus. A Nymphet’s Guide. Wattpad, 2019. Read here

Durham, M. Gigi. The Lolita Effect: The Media Sexualization of Young Girls and What We Can Do About It. New York: Overlook Press, 2008.

Final Girl Digital. “Why Lolita Is Impossible to Adapt into Film.” YouTube, 2024. Watch here

Fingerhut, Joerg, et al. “The Aesthetic Self: The Importance of Aesthetic Taste in Music and Art for Our Perceived Identity.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, 2020. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577703

Gay, Roxane. “Ugly Beautiful.” In Lolita in the Afterlife: On Beauty, Risk, and Reckoning with the Most Indelible and Shocking Novel of the Twentieth Century, ed. Jenny Minton Quigley. New York: Penguin Random House, 2021, pp. 49–58.

Gill, N. S. “Who Are the Nymphs in Greek Mythology?” ThoughtCo., 2024. Read here

Harrison, Lucia Rhiannon. “The Origins of ‘Coquette’: Infantilization, Girlhood, and Morality in Fashion Trends.” Bare Magazine, 2023. Read here

Horses. “Lolita: The Worst Masterpiece.” YouTube, 2024. Watch here

Zimmer, Dieter E. “Covering Lolita.” dezimmer.net, 2014. Read here

Morse, Erik. “A Portrait of the Young Girl: On the 60th Anniversary of Lolita.” LA Review of Books, 2015. Read here

Nabokov, Vladimir. Lolita. London: Penguin Modern Classics, 2015.

— The Annotated Lolita. London: Penguin Modern Classics, 2000.

Nymphetyaya. “I Was a Daisy Fresh Girl and Look What You’ve Done to Me.” Tumblr, 2017. View post

Ratna, Lawrence. “Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: The Representation and the Reality.” Journal of Humanities and Social Science, vol. 25, no. 8, 2020, pp. 22–31. DOI:10.9790/0837-2508072231

Russell, Kate Elizabeth. My Dark Vanessa. London: 4th Estate, 2020.

Sebastian, Lola. “We Need to Talk About Lolita.” YouTube, 2019. Watch here

Silva, Michael Da. “On the Subjective Aesthetic of Adrian Lyne’s Lolita.” Senses of Cinema, 2009. Read here

Steph Green. “The Troubling Legacy of the Lolita Story, 60 Years On.” BBC Culture, 2022. Read here

Thompson, Kenn. “Vladimir Nabokov’s Fascination with Lepidoptera.” History of the Worlds, 2024. Read here

Theresa, Jordan. “The Lolita Resurgence... When History Repeats Itself.” YouTube, 2021. Watch here

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Nymph (Entomology).” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2024. Read here

Filmography

Lolita. Dir. Stanley Kubrick. MGM, 1962. Available on Amazon Video

Lolita. Dir. Adrian Lyne. The Samuel Goldwyn Company, 1997. [DVD release]